The Place to Be – the rise of place-based writing

Recently I joined veteran travel journalist Simon Calder and ex-BBC producer Mick Webb again for their popular podcast on travel, You Should Have Been There. The topic they put to me was arresting, and one I hadn’t considered before: how do non-fictional and fictional journeys differ, in literature? Are so-called travel writing and writing about travel in novels really so different, Calder and Webb proposed, and which mode might be ‘better’?

I’ve been thinking a lot recently about writing about place, and in fact am working on a book about this. ‘Place-based’ writing has replaced travel writing as a category, in part because of concerns about travel writing’s legitimacy, specifically its roots in colonialism. There are other, linked, suspicions about it: questions about who has the socio-economic means to travel and the clout to have their voices published, as opposed to the people who actually live in the places they write about. Travel writing has long been about means and access, one way or the other, as well as steeped in the project of translating a ‘foreign’ reality to a better-provisioned, often complacent audience.

On the other hand, most of us are travellers, at some point in our lives. Experience is often organised around or shaped by journeys, whether physical or metaphorical. During the Coronavirus pandemic the importance of travel to our sense of well-being and our ability to learn and understand the world became starker. Place-based writing could be the bridge we need to move on, aesthetically and formally, to place place (repetition deliberate) at the centre of the story. Place-writing also has vectors into nature writing and writing about the environment. As a category its main appeal is to try to render our affinities with physical places and to capture the subjective reality of how we respond to physical locales, whether landscapes, areas, nations or notional places such as ‘home’.

My research for the podcast sent me to my bookshelves, to scour them for examples of both travel writing and writing about travel in fiction. The worthwhile ‘travel writing’ was easy to spot. From classics by pioneering women writers (No Hurry to Get Home by Emily Hahn, West with the Night by Beryl Markham) to those who were also novelists but who excel in writing about place such as Bruce Chatwin and DH Lawrence, to under-appreciated writers such as Shiva Naipaul and his classic on travelling in east Africa, North of South, to reportage by George Orwell and Martha Gellhorn, there were plenty of examples.

Fiction was harder. I picked out A Fine Balance by Rohinton Mistry, for its evocations of India and the migrant Canadian experience, to modernist classics such as Death in Venice by Thomas Mann and Good Morning, Midnight by Jean Rhys, in which Venice and London supersede setting to become agents and even characters, to Paul Bowles’ commanding, spectral Sahara desert in The Sheltering Sky, to WG Sebald’s mephitic Norfolk coast in The Rings of Saturn.

At the risk of disappointing Mick and Simon, I decided it was impossible to choose which mode of writing about so-called travel was best. But I had a more profound and useful realisation: as our awareness of climate change and the seismic footprint of our influence on the non-human world grows, place-based writing has a role in transcending genre, to become part of an intellectual and aesthetic shift toward transhumanism, in which writing migrates away from focussing solely on human experience, conflict and consciousness.

On a dark late afternoon just before Christmas, we met to record the podcast in the quietest public hotel bar we could find, in Bloomsbury. I previewed to Mick and Simon my theory that place functions very differently in non-fiction and fiction. In writing about place, including travel writing, the journey is the destination and the purpose; the journey is everything. People read travel literature for a number of reasons – vicarious movement is certainly one of them – but the most common is, I think, to see a place through someone else’s eyes. Any good writing allows the reader to see the world anew. In fiction on the other hand, place functions as a metaphor. (Metaphor is in fact the only real difference between fiction and non-fiction, along with character.) In novels and short stories, human dilemma generates the necessary drama. Place or travel are often either a backdrop or a narrative crutch. Moving people around is a way to get something to happen or to generate dramatic heat. With place-based writing, the human consciousness, in the form of the writer and the personages they present, real, fictional or composite, share the fore-stage with place.

The fact is, place is hard to render in writing. It is not about description, adjectives, attention to detail, observational prowess, interpretive writing, specificity, knowledge of Linnaean classification systems, botany, zoology, history, although such tactics abound in nature writing. I am not immune to the weird rapture of taxonomy. But naming is not the same as knowledge, it is only its detritus. What it takes to write about a place is to tune into its frequency. Like people, places broadcast a certain energy which is utterly unique. Drama must be excavated from place; it is there, latent, but it must be discovered. It’s a matter of focus. The animate does not have the same energy as the inanimate; one is kinetic, unstable, and the other eternal.

During our conversation before we began recording, I mentioned a book to Mick and Simon that I admired almost above all others for its rendition of place: Tristes Tropiques, Claude Levi-Strauss’s anthropology-memoir-travelogue masterwork. In it, he offers a masterclass in what is known in ethnographic circles as thick description. In ‘’Part Two: Travel Notes”, over nearly ten pages Levi-Strauss documents a sunset he witnessed – or experienced, better said – in the middle of the Atlantic while travelling by ship from Marseille to Santos, Brazil:

‘At 5.40pm the sky, to the west, seemed to be cluttered with a complex structure, which was perfectly horizontal in its lower part, like the sea, and indeed one might have thought that it had become detached from the sea through some incomprehensible movement upwards from the horizon, or had been separated from it through the insertion between them of a thick, invisible layer of crystal…still higher in the sky, streaks of dappled blondness were decomposing into nonchalant twists which seemed devoid of matter and purely luminous in texture.’

You can hear the scientific exactitude in his prose. He mixes empirical, scientific rationalism (‘perfectly horizontal’) with a sense of astonishment, even scepticism (‘incomprehensible movement upwards’) that the natural world could produce such a phenomenon. He records, with a doubtful rectitude, his enchantment:

‘Night is the beginning of a false spectacle: the sky changes from pink to green, but this is because certain clouds, without my noticing it, have become bright red and so, by contrast, make the sky seem green, although it was undoubtedly pink, but so place a pink that he shades could not withstand the extreme intensity of the new colour, which, however, had not struck me, sine the transition from gold to red causes less surprise than the transition from pink to green. And so night comes on as if by stealth.’

Note how he records the gaps in his perception, his lapses of attentiveness, his inability to process what he sees. Unlike most contemporary nature writers, he doesn’t hesitate to admit his lack of certainty while recording the sublime experience of being stunned into incomprehension by the effortless beauty generated by nature. Note too how the twist in the cloud Lévi-Strauss sees is not delicate or wispy, but nonchalant – a human characteristic of devil-may-careness donated to a pile of vapour. We are alive in a zone of ephemerality, uncapturable, he suggests, and this transient ferocity is what distinguishes the human will from the vast arena it cannot control. Lévi-Strauss not only transports us to the nadir of a tropical afternoon at sea. He builds it, like a bricklayer, piece by piece. In his hesitant, stunned prose we are caught in the reverse thrust of the sunset’s vortex. We hear the fume of the eternal in his forensic notes, the understanding that places carry on, implacable, without us – especially wild and inaccessible places.

Places just are, ultimately. To over-interpret them is another form of appropriation, even a colonisation of a kind. Sometimes, a writer can read, translate and render the spirit of a place. This is the task; to interpret the quality and intensity of the land, to diagnose what it is trying to tell you, but more than this, to simply listen to the frequency of its being.

You can listen to our podcast here: https://anchor.fm/youshouldhavebeenthere/episodes/THE-BEST-TRAVEL-FICTIO…

Wanderings: Elizabeth Bishop’s ‘travel writing’

An essay on travel, the pandemic and Elizabeth Bishop’s poetry published in the Literary Review of Canada, 2020.

Think of the long trip home.

Should we have stayed at home and thought of here?

Where should we be today?

Is it right to be watching strangers in a play

in this strangest of theatres?

— Elizabeth Bishop, ‘Questions of Travel’

On February 29, the calendar’s most elusive date, I arrived in São Paulo from my home in London. Although the morning was cool and overcast, emerging from the northern hemisphere winter into the subtropics felt like awakening from a cryogenic slumber. During the flight, I had watched Orion cartwheel across the sky as we journeyed down the Atlantic Ocean. I am a hardened traveller, but each time I fly I find it a miracle that we are able to propel ourselves through space with such velocity and relative safety. Also, I know how long the alternative mode takes…

Read the full essay at: https://reviewcanada.ca/magazine/2020/09/wanderings/

Sightlines – commemorating WG Sebald’s 75th birthday

Two recent exhibitions and a flurry of symposia in his home town of Norwich commemorate what would have been the writer WG Sebald’s 75th birthday. Lines of Sight exhibits photographs from Sebald’s research for Rings of Saturn: An English Pilgrimage (1995). A separate exhibition at the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts at UEA presents photographs from his research for his novels Vertigo (1990) and his final major work to be published in his lifetime, Austerlitz (2001). At the same time a symposium brings some of Sebald’s translators to UEA to consider the relationship between image, text and translation in his works. My review of the exhibitions and a meditation on Sebald’s lasting influence is published in The Spectator: https://www.spectator.co.uk/2019/05/from-haunted-to-haunter-the-afterlif…

Borderland: Walking La Ruta Walter Benjamin

‘Chemin Walter Benjamin’ reads a lemon-hued sign, half-hidden under tree branches. A shaded path heads alongside a house in the hamlet of Puig del Mas in southernmost France. The early July morning is already hot. Ahead, in the foothills of the Pyrenees, are the steep vinyards of the Côte-Vermeille, a wine-growing area which produces, among other varieties, Côtes du Roussillon.

We have come to walk this 17 kilometre-long route over the Pyrenees, crossing an unmanned section of the border from France to Spain. It is from Banyuls-sur-Mer, a resort town two kilometres away from the trailhead, where we depart, bidding goodbye to a small French Navy destroyer anchored, seemingly permanently, in the bay – a reminder that frontiers within a supposedly borderless Schengen zone in Europe are under a new level of scrutiny.

Like many who take the circuitous route over the mountains, we are doing the walk in a conscious commemoration of the last steps of the German literary critic and philosopher, Walter Benjamin, whose name the path now bears. Benjamin was one of many refugees who escaped the Nazis via this steep and at times dangerous route, a former smuggler’s path which winds the interior, shying away from the better-known routes near the sea but which the Vichy collaborationist regime established after the German invasion of France in 1940 had under surveillance. Hundreds, perhaps even thousands (no number has been recorded) of people successfully escaped France and Europe this way. Of all of those who took it, Benjamin is the only one who is known not to have survived to reach freedom.

*

We start the walk late, at 8am, as we have had to prepare film equipment and props for the short film we will make about the crossing. We are also producing a series of still images, photographs of Benjamin’s own words in the form of fragments of text taken from his The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, scattered through the landscape as we walk.

At first the path is a relatively gentle ascent, winding through vinyards of a plastic, almost fluorescent, green. The area is a hive of activity, for a Sunday morning. As we walk uphill a buzzing noise reveals a drone flying just overhead. Slowly it descends, the blinking red eye of its camera turned on us, until it is plucked from the air by a man in an SUV dressed in a T- shirt and shorts, his car parked in an alcove underneath our path. Workers in orange high visibility trousers come and go in a small van with cut grass and brush in the back. They make several passes underneath us. Further up the mountain, a wiry endurance runner flashes past us on a nearby asphalt path, so quickly one of our group does not see him.

For the rest of our walk we see no-one. Once above the vinyards the path rises steeply, zig-zagging up the mountain. We ascend five hundred metres in two hours. Parts of the trail are near vertical and we have to scramble almost on our hands and knees. Each step has to be judged over sharp undulating rocks. Steep drops await. Any fall on this terrain would mean an injury.

In the émigré community and the French Resistance the trail was known as Route F, for Lisa Fittko, the woman who guided Benjamin and hundreds of others over it two or three times a week for seven months during 1940-1. At the time the narrow track of rock and scree was the only escape route from France. Many of the refugees’ ultimate destination was the United States, which had issued Benjamin an entry visa. They would travel to Barcelona, then Madrid, then to Lisbon, from where they would take a ship to the New World.

In France the path is marked by intermittent yellow signs of the kind we encountered in Puig del Mas. There are also Route Nationale signposts, which announce the distances we must yet traverse to reach the Coll de Rumpissar, the summit and site of the land border between France and Spain. What really guides us on the trail when we are uncertain or nearly go off in the wrong direction are the black and yellow bars painted on rocks, the colours of the Grande Route 10, which crosses the entire spine of the Pyrenees from the Atlantic to the Mediterranean.

We reach the summit at lunchtime. Our progress has been slow, impeded by our equipment and the need to stop to film footage every kilometre or so. On the top the wind is a thin groan. Succulents and cactus line the lip of the mountain. In the sky two jets race each other, flying parallel to Madrid or Barcelona, perhaps.

Although Lisa Fittko had scouted out the lower regions of the path before September 25th 1940, the day Benjamin, accompanied by a fellow refugees photographer Henny Gurland and her 15 year-old son Joseph, walked it, that was the first day she guided people all the way to the border. In her memoir, Escape from the Pyrenees, she writes: ‘Finally we reached the summit. I had gone on ahead and I stopped to look around. The spectacular scene appeared so unexpectedly that for a moment I thought I was seeing a mirage … the deep-blue Mediterranean … “There below us is Portbou!”

The view is as stirring as she describes. To our left is the Torre de Querroig, a remnant of a medieval castle dating from the 13th Century. The summit is the only place on the trail where you can see France and Spain in stereo, taking in Banyuls and Portbou in a glance. In the distance the peninsula of Cap de Creus fingers out into the Mediterranean. Behind us, the French side is less steep and wild, its hills embroidered with vinyards where the Spanish side is uncultivated, thick with pines and cactus. The border is more than a line on a map; it spells a different climactic zone.

From the summit the path is renamed the Ruta Walter Benjamin and red and blue signs labelled ‘Portbou’ guide us. At intervals along the path we find information lecterns which tell the story of Benjamin’s last walk in English, Catalan and Spanish, but which are nearly illegible, faded by the sun and scoured by wind and rain.

The descent is tougher than our journey up. We often slip on loose scree with no secure foothold. It has the aspect of a trail meant to be used in one direction only; I can’t imagine how hikers would make it up the stretches we skid down. The real marvel is how refugees, many of them urbanites recently arrived from Paris or Marseille and without our state of the art North Face walking shoes and six litres of bottled water, were able to traverse this path with only bread, tomatoes and black market marmalade to share between them. As we walk I imagine their fear of the real probability that around any corner they might encounter a border guard who would almost certainly return them to France, a country which had become a death trap.

*

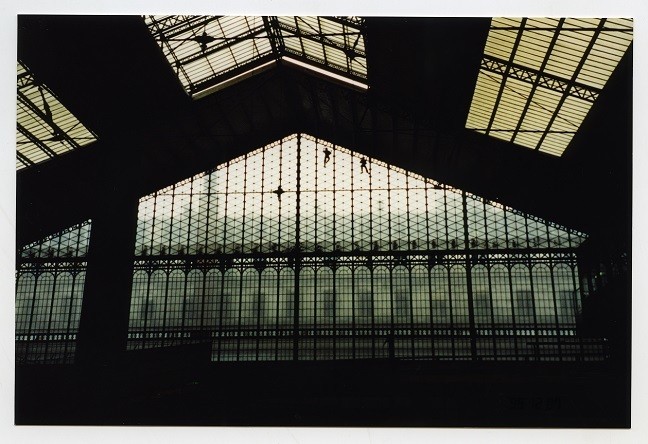

We arrive in Portbou just before five in the afternoon. The émigrés’ arrival would have been not very different from ours, apart from the Citroen Cactuses and the Renault Méganes parked inside the hulking Victorian-era tunnel which leads from the mountain into the town.

They struggled into Portbou in the afternoon on September 25th 1940, passing underneath the railway sidings, emerging from its darkness into a blaze of light, a small avenue lined by pollarded plane trees and, in the distance, a flash of blue Mediterranean.

It took all of Benjamin’s small group’s remaining strength to ascend the vertiginous staircase into the station. The were badly dehydrated, but they agreed that it was best to present themselves to the customs office to get their papers stamped for onward travel as soon as possible.

The customs offices in Portbou rail station are still there, although long closed. You can look through smudged, cracked windows to see ornate interior depots with ceilings three stories high. The Spanish border presence on the day we visit consists of a lone Guardia Civíl officer with an Argentine accent who occupies a dusty desk with a telephone, as if the computer era had never happened.

It was in an office much like this one where Benjamin’s group were informed that the Spanish government’s position had changed. Franco’s regime would no longer recognise the papers of those who had crossed the border illegally. The officer told them they would be returned to France the following day. There the group faced immediate internment by the Vichy regime.

The group was put under armed guard in the Hostal França for the night of September 25th. The building is still there, in a small plaza. It looks tiny and shabby. In fact, with its mini-ramblas, tight semicircular bay and low-rise houses, Portbou has a miniaturist quality, like an abandoned architect’s scale model for a much larger city. Apart from the rail station, whose scale is that of a train station in a major metropolis: Paris, or Barcelona, say, a remnant of an era when borders were physical, and not dispersed in space and time via technology.

Some time in the night of September 25th or in the early hours of September 26th Benjamin took from his pocket the morphine pills he had been carrying with him since he left Marseille – he had ‘enough to kill a horse’, according to Arthur Koestler, Benjamin’s friend and fellow émigré. The next day the refugees woke to the news that the policy had changed. They would be allowed passage after all. Benjamin did not respond to knocks on his door, to urgent entreaties to get ready for the journey onward to Barcelona.

If Benjamin had arrived in Portbou one day earlier, before the edict preventing illegals from making the passage through Spain, he would have lived. One day later, when the decision, or mis-communication, had been forgotten, he would have lived. Knowing this now, it is difficult not to think of the workings of fate. Before making the arduous journey over the mountain, Benjamin had been stripped of his German citizenship, had his apartment in Paris searched by the French in the first hours of German occupation, and had lived at 28 different addresses in his seven years of exile. As a German Jew, if he remained in France his most likely fate was to be interned in a transit camp before being shipped to a concentration camp. There his life would end.

Route F was his only chance. He seized it, without knowing how it would end; in mis-communication, confusion, exhaustion.

The day his body was discovered, bills were prepared, in pesetas, for Benjamin’s stay. His uneaten breakfast was charged. The coffin maker’s detailed bills have also come to light. The US dollars in his suitcase went some way to covering his expenses. His fellow escapee, Henny Gurland, provided the rest from her own funds.

Portbou and its railway station in 1940.

*

Earlier that afternoon we emerged from our walk via the darkness of the long viaduct blinking into the light. At the mouth of the tunnel a young woman sat on a plastic chair, staring into her phone. There was no need for a parking attendant, as parking in the tunnel was not charged. Opposite, a man dressed in the blue and yellow high visibility overalls of a streetcleaner (it was a Sunday) lounged against the wall of the tunnel, eyeing us closely. As we appeared he stepped forward. For a moment he seemed to be about to say something to us.

We had exhausted our water supplies and needed to restock. We veered into what we took to be a shop and which turned out to be a liquor store, where we bought two one-litre bottles of Font Vella.

Two bandy-legged men manned the liquor store. I wandered along the aisles. There was a surprisingly vast range of litre and quarter litre bottles of hard liquor, gin and vodka varieties I had never heard of.

‘Would you mind coming out of the shop,’ one of the bandy-legged men said to me in Spanish. ‘I’m worried about your backpack.’ He pointed to my day-pack which, while full, hardly posed a threat to his bottles.

‘Don’t worry,’ I said. ‘I’m not going to knock anything over.’

His eyes flickered. I understood his discomfort was not really about my backpack.

We left, climbing the stairs – another near-vertical ascent – to the rail station. On the way I pointed to my companions out the former Hostal França, where Benjamin had died. We did not stay to ask if we could go in.

It was my fourth visit to Portbou. It’s hard to know if it is the place itself, hemmed in by two high hills in the last gasp of the Pyrenees, or if it is the shadow of Benjamin’s death which is responsible for the instinctive dread I feel in the town. It is a fascinating place, in many ways, with its belle époque architecture, a fusion of France and Spain, artist Dani Karavan’s spectral monument to Benjamin on the hillside, its faded colonial streets which make it look, at certain angles of the day and night, like a town in Panama or Nicaragua. But there is a surly, obdurate, energy to the town. Perhaps all border towns have this, an agglomeration of the anxiety of people whose lives have been truncated by border zones and the authoritarian function of such places.

Our journey that day had been accomplished with a deceptive freedom. We walked across the mountains and the border unchallenged by any human being, with the comfort of our maroon-covered passports in our backpacks should anyone demand to see them. We had been guided with the help of Google and GPS; we’d had a mobile phone signal nearly all the way. We were easily tracked (and perhaps we had been) should the authorities had any interest in doing so.

Yet borders are proliferating. On October 1st this year Catalunya will hold an independence referendum vote. It is possible that a different kind of border will one day be demarcated: that of an independent nation, the first such secession in western Europe since Belgium seceeded from the Netherlands in 1830. And in less than two years’ time our (British) European Union passports will change colour, signifying the greatest repeal of citizenship since the Nazis passed the Nuremberg Laws in 1935 revoking the citizenship of German jews. A new web of borders will appear for us in an instant.

Earlier that afternoon, as we neared Portbou on a relatively easy road, thankful we were no longer heading downhill at a forty-degree angle, we reflected how we might face even greater challenges to escape than Benjamin and his contemporaries did, should the tables turn and we become migrants ourselves. The border is everywhere, now, thanks to biometric passports, mobile phone GPS tracking, thermal imaging cameras – and, who knows?, even drones – and we might be only its captives-in-waiting.

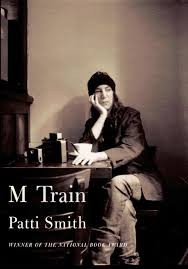

M is for Memoir – what makes memoirs work?

Christmas is upon us, and this year I’ve been given two memoirs as gifts: Instrumental by James Rhodes and M Train by Patti Smith. At the same time I am at last last getting round to reading Geoff Dyer’s Out of Sheer Rage, an anti-memoir about failing to write a critical study of DH Lawrence. Earlier this year I read Helen MacDonald’s affecting and elegant H is for Hawk, and I am at the moment re-reading Aidan Hartley’s The Zanzibar Chest, a memoir which, when I read it first two years ago, I thought monumental, epic – in a league of its own. These books have nothing in common apart from the label memoir, which has become a sort of default category for the uncategorisable.

I am asking this question, of what makes a good memoir, somewhat belatedly, given that I am about to publish my first memoir in a few months. Let’s take the measure of this changeling category. Memoirs have lately become ambitious. No longer is it enough to tell a personal story. They are now charged with providing much more bang for one’s buck, even if their basic currency remains personal transformation. At meta-level, memoirs are still about a journey from innocence to experience. Challenges are met and overcome; understanding and reconciliation are the spoils of a fight played out against a canvas of larger events and in the dank antechambers of the inner life.

Memoirs also require memory work; harmony is also achieved through the pas-de-deux between the past and the present self. The narrator-self in memoir is a hall of mirrors, casting and then revising its reflections on the past. The narrating self knows the future while the past self is unaware of what is yet to come. This creates an instant pathos and also a dynamic narrative tension.

But beyond this basic narrative premise, vexing aesthetic questions lie. Who narrates a memoir? It would seem obvious: the writer, the self. But I think it is more accurately an alter ego. This voice is that of the writer, and yet also not. As Ian Thomson, my colleague at UEA and author of several works of non-fiction has said, the main challenge in writing a memoir is finding a ‘congruent’ voice. It’s an unexpected word for literary criticism. Congruence is usually used in maths and geometry. It means ‘agreeing’, ‘accordant’, and ‘coinciding at all points when superimposed.’ The congruent voice is, I think, one that changes as events happen but which is also consistent enough to give a book coherence. This ‘I’ is the authentic voice of the author and simultaneously a literary construct. If a writer can achieve this amalgam without sounding false, studied or precious, while also adopting a voice which the reader will want to listen to for the course of a book, then congruence has been achieved.

Dyer’s Out of Sheer Rage is the most non-conformist book in the crop of my current memoir reading: not so much memoir as literary auto-criticism. Patti Smith’s impressionistic, episodic M Train, which has won the National Book Award (US), is, as Smith writes, about ‘unexpected encounter[s] that slowly altered the course of [one’s] life.’ James Rhodes’ Instrumental is subtitled ‘A Memoir of Madness, Medication and Music,’ and duly tackles all three Ms. The Zanzibar Chest, meanwhile, spirals beyond the perimeter of its author’s life to encompass wars in Somalia, Ethiopia, Rwanda and Burundi, witnessed during his years as a reporter, as well as his father’s life in Yemen and later, Tanzania and Kenya.

The selves in these books – experiencing-selves, narrating-selves, watcher-selves – ebb and flow. The exact quotient of inner life matches each book’s spirit (melancholic and introspective, Smith writes, ‘I skip Thanksgiving, dragging my malaise through December, with a prolonged period of enforced solitude, though sadly without crystalline effect.’) Memoirs need a voice which transmits the sensibility of the consciousness that produced it, and also rings in the head of the reader in a way that does not grate. The voices in these books are all completely distinct: Smith – ruminative, grave, floaty; Rhodes – irascible, frenetic and caustic; Dyer – elliptical, indecisive to the point of neurosis; Hartley – ascetic, stern, undeterred.

Voice and narration are only half the task, however. For plot, a memoir would seem to have an obvious design: the writer is governed by what actually happened. But this is far too simplistic. Events in memoir are not only happenstances but a patterning. The mind is an unconscious seeker of patterns; it is the memoir writer’s search and revelation of an underlying structure to existence – and therefore, by association, the suggestion of a logic in the seeming inchoate distribution of events in all our lives – which creates a formal and aesthetic pleasure in reading memoir.

My feeling is that, however insightful or well-written, memoirs become exceptional when they are built on a purpose larger than the journey of the self; in doing so they posit a theory of existence as much as tell a story. In Smith’s’ M Train, her affinities build a lattice of enigmas which seem to underpin her existence: the obscure Continental Drift Society, which espouses a vaguely esoteric approach to the hard science of oceanography, tectonic plate movement, and meteorology; the writings of Jean Genet; dreams. A lesser mortal would not be able to get away with such a wayward, abstruse narrative approach. But Smith’s Sebaldian vignettes are also historical document, a testimony to a life lived at the epicentre of 1970s and 80s counter-culture. The Zanzibar Chest, meanwhile, is an epic, investigating how the currents of history and individual lives collude and retreat, and even the nature of history itself, as played out through savage conflict. Hartley’s narrating self is somewhat effaced by his sense of purpose in his role as a witness.

But beyond all this technical astuteness is a more subtle formal challenge which must be mastered. If a memoir is to work, the book’s structure has to mirror and express the memoir’s sensibility. In Rhodes case, his chapters are ‘tracks’; ‘Track Four: Bach-Busoni (James Rhodes, Piano)’ is about how a dark, furtive score became his refuge, just as he describes the ongoing abuse he suffered as a child. In M Train, Smith has vignette-chapters whose titles could easily be songs – ‘How I Lost the Wind-Up Bird’ and ‘Road to Laroche’ – and which advance her thesis that life is a series of parsable conundrums. Hartley’s memoir is structured in long chapters with a single image as a frontispiece, a suitable scaffolding for its epic, formal exploration of the complexities of history and politics. Meanwhile Out of Sheer Rage begins as a paragraph-free frustrated rant, which settles into the stately, relentless cadence of the state of bored possession.

For my memoir Ice Diaries: An Antarctic Memoir, which will be published in March 2016, the substance which the book is about – ice – gave me its formal and emotional structure. Each chapter is headed by a term from sea-ice nomenclature, an official document which describes the kinds of ice encountered at sea and on land in the polar regions (there are over a hundred). The ice term which heads each chapter embodies the emotional energy of what takes place in its confines: ‘hummock’, for example, is a pressured, ridged ice that forms at the base of glaciers typically, the product of severe stress.

This is what memoirs do, ultimately, and perhaps the key to their popularity: rather than tell a personal story, they uncover the pattern of reality – the real story, so to speak – obscured by the life one lives, which is in the end only a decoy for a more profound truth. To quote a popular Facebook homily, memoirs demonstrate that the journey really is the destination.

Everything is happening now

The Present Tense in Fiction

I have always had trouble locating the present moment. This is worrying, given that we are supposed to live in the present. If the present moment is our only home but I can’t grasp it, then what’s left to inhabit – a continual reminiscence or an anticipation of the future? But the past is over and future is fictional – it may or may not exist.

To try to grasp the present moment I sometimes turn to fiction. Fiction is experiential and emergent, no matter what tense it is written in. But fiction and the present tense have an uneasy relationship. At the moment novels and fiction written in the present tense seem to be proliferating, not least on my desk – two of the three novels I am currently reading are written entirely in an unfolding present moment. Is the current taste for present tense fashion, an effective literary device, or does it signal something innate about our cultural moment?

In 2010, a spat about the present-tense erupted in the press; it was the kind of controversy that must have seemed arcane and cloistered outside of literary circles. In that year, judges on the Man Booker Prize became worked up about the fact that three books on the shortlist presented a confluence of present-tense narratives – C, by Thomas MacCarthy, Room by Emma Donoghue and In a Strange Room by Damon Galgut. Philip Pullman, one of the judges, commented publicly this obsession with emergence, calling it a ‘wretched fad’ and accusing its practitioners of ‘an abdication of narrative responsibility.’ Pullman decried the abandonment of the past tense in all its guises – pluperfect, imperfect, simple and historical pasts.

It’s true that the past tense has more flexibility and more tenses; then why use the present at all? The present tense is a literary device and like all devices is employed for effect. The key is to be found in the term itself – tense governs tension. As a random sample, here are a couple of lines from Helen Walsh’s recent novel, The Lemon Grove, which employs the present tense to gripping and eloquent effect: ‘From nowhere, she feels the air-rush of someone coming up right behind her. She clutches her handbag to her chest and tightens her elbow to her ribs. A hand grabs her by the shoulder and pulls her back. It’s his; him.’

The present suits Walsh’s 275 page novel, which is set over a fortnight of a summer, and has the feel of a suspended moment, a fever dream. But, as with any device, there are advantages and disadvantages, restrictions and freedoms, which the writer must carefully consider, especially for a novel-length piece of fiction. But the choice of tense also has wider implications and effects that reach far beyond technique and into the real of the metaphysical. Which brings me back to my lifelong deficiency in truly inhabiting the present.

The present tense, neurologically speaking, lasts between 1.8 and three seconds. Experimental psychology experiments show that any stimulus lasting more than three seconds can’t be grasped by our consciousness; any longer, and we begin to consign it to memory, memorializing, correcting, adjudicating – or, conversely, we begin to anticipate the next moment, already congealing on the outskirts of the present. We are living in a current of past and future moments masquerading as presentness.

But also, what we take to be the present is a very slightly delayed past. The reality of the moment is like a tape delayed broadcast, carefully vetted by the brain for information before it reaches us. Neurologist and writer David Eagleman describes it thus: ‘[The brain] is trying to put together the best possible story about what’s going on in the world, and that takes time.’ This is why, Eagleman argues, that in life- threatening situations, time seems to slow down because the brain really is slowing it down; it is thinking very hard about what is happening and what the possibilities for action are. The present tense is an edited past and the moment we think of as coming next has in fact already happened. In his seminal essay ‘The Dimension of the Present Moment’ Czech poet Miroslav Holub doubts whether the present tense exists, at least in life. ‘I strongly suspect that we simply happen in segments and intervals,’ he writes. ‘We are composed of flames flickering like frames of a film strip in a projector, emerging and collapsing into snake-like loops on the floor, called the just-elapsed past.’

The present tense in fiction is simultaneously constructed from this cognitive lie but also ignores it. The present tense slows down time long enough for the characters – and by association the reader – to inhabit it. But in privileging the present moment, the writer denies any possibility of perspective or choice in how to view the proceedings. Jenny Hendrix, writing in the New Yorker blog, comments ‘the present…doesn’t allow us this process of choice: it is happening now, and so it is the only thing that can happen. Everything is given equal weight because we haven’t yet had time to judge its relative importance.’

The corralling of the reader into a perpetually emergent present tense runs the risk of exhausting her. The equal weighting of each occurrence that Hendrix notes is echoed by Pullman: ‘If every sound you emit is a scream, a scream has no expressive value. What I dislike about the present-tense narrative is its limited range of expressiveness. I feel claustrophobic, always pressed up against the immediate.’

For much of the history of the novel in English, the present tense has been employed in a duet with past tense narration, as in Dickens’ Bleak House. In this mode, bookended by the past, it seems to come into its own; it allows the present to be used to what I think is its best effect: an oration, often rhapsodic, signaling intensity and significance, which emerges out of a past tense narration, for effect. The reader is exhorted to experience the moment as the character or narrator does, on the same level of consciousness. There is a captive, suspended quality to the present. Its cinematic parallel is the hand-held camera.

As lecturers in creative writing my colleagues and I are often called upon to dissect the relative virtues and pitfalls of tense. ‘Tense can dramatically change the style of a story,’ says Henry Sutton, Senior Lecturer in Creative Writing on the MA at the University of East Anglia. ‘Present tense can be lively, urgent, in your face almost, and more contemporary-feeling. It demands immediacy. If your fiction/story doesn’t want or feel to be any of those things then you might have a problem using it,’ he says. ‘Meanwhile the past tense can command a sense of authority, seem a little more traditional, and conceivably distant.’

Julia Bell, who teaches at Birkbeck, has written several young adult novels using first-person present tense narration. ‘I think that life has to be lived in the present tense so it’s a simulation of that, up to a point,’ she says. ‘But it’s also a sleight of hand because you are persuading a reader that narrator is telling the events of the story as they are happening in a kind of running commentary – which in itself can be exhausting. I’ve used it in my novels because it’s the voice of a teenager – teenagers don’t really have a past tense yet – the world is very present to them.’

Urgency and immediacy – these are the strengths of the present tense. But also a sense of a breath held for too long. As Philip Hensher commented during the fracas in 2010, the present tense is often turned to provide a quick tonic for writing which lacks conviction and tension. ‘Writing is vivid if it is vivid.’ The present tense used to be a rarity in fiction, Hensher points out. Its use alone signaled that something important was about to happen, it exhorted the reader to sit up and take notice. But if we are kept in a constant state of anticipation and alertness we begin to fray at the edges, to fumble for distinction and importance. In a perpetual present tense the counterpoint effect of pitting present against past is lost.

The present tense may also somehow reflect a contemporary experience of being. Richard Lea has commented in the Guardian that ‘as the pace of modern life accelerates, the present that we’re all living in seems much more immediate, much more fragmentary. In a world of Watergate and Wikileaks we’re much less prepared to accept a final version, an official story. The internet, mobile phones, Twitter: all gnaw away at our capacity to reflect; all push us to experience life as a series of unconnected moments.’

The past will soon be edited to fit our expectations, and the future will certainly contain less errors. In the meantime we live stranded in this interstitial place called the present, truncated by a restless consciousness, but which simply is. There is no time for editing, no time for hope. This is likely why it appeals to readers, in fiction – it is like watching a film, a life emergent and becoming, unslurred by the false consciousness which governs the real business of living.

What I feel, when reading the current crop of present-tense novels that grace my desk, is that the present promotes the emotional frequency of the confessional, and within it – as in many self-admonishments – an appeal for understanding, perhaps for absolution, although from what is not clear. From fate, perhaps. It is always happening, it comes in a rush, it is hard and fast, as life itself is: a hit-and-run stalker, a chaperone, a curious shadow, no friend, necessarily but the water we are moving through. An appeal. I didn’t know, because it was happening to me. And in its false innocence we recognise our predicament.

Consciousness, character – and conscience – in the novel

Henry James’s Portrait of a Lady is – along with Wings of the Dove – his most morally searching novel. I recently returned to the novel for my seminar on consciousness, character and the novel on the Theory and Practice of Fiction course I am teaching this year on the University of East Anglia’s creative writing programme.

There is a very famous scene which takes an entire chapter, Chapter 42, to play out. On the surface, not much happens. The heroine, Isabel Archer, sits by the fire in the house she shares with her husband, Gilbert Osmond. In the first part of the chapter her husband attempts to manipulate her into furthering the marriage of his daughter Pansy, Isabel’s step-daughter.

Osmond upbraids Isabel for her hesitation in setting in motion a marriage which she knows will not work. Her husband’s parting shot as he takes leave of her is that she ‘find a way.’ For the rest of the chapter Isabel thinks, and the fire burns low. The candles diminish. She stays there, alone by the fire, until dawn. At the end of the chapter, she rises and leaves.

In action terms, it’s not Die Hard. But this chapter is the fulcrum of the novel. Through the course of that long night, James sloshes through the turmoil in Isabel’s mind as she sifts through clues, realisations, fragments of understanding, discarded instincts, her own motivations, to try to understand how she has tilted her toward this moment of misery and – she begins to understand – betrayal.

The scene is demanding to read. It is dense with thought and recollection. It presents us with one of those controlled, supernaturally articulate furies of James, when he writes about a character’s inner upset. What it achieves, I think, even more masterfully than to show a woman grappling with her predicament, is to chart how the process of how Isabel Archer comes to understand consciously the things she already knew unconsciously – about herself, her husband, her marriage, her lot. Conscience is thought to be a project of the conscious mind, but it might more properly reside in the unconscious, where it is formed by sparks and flares of instinct. Above all else, Portrait of a Lady is a dramatisation of one woman’s reckoning with conscience, and how, having discovered it, she must pit it against her desires and instincts.

In class that day my students and I considered this topic of consciousness, character and (although it isn’t in the seminar title) conscience as a vehicle to think about our instincts, motivations and ambitions as fiction writers.

The novel is a way to investigate what it means to be alive. The novel can also be a form of abstract thought, given life and depth and feeling through the creation of people who don’t exist. We wondered, why are we bothering to do this? Creating characters, especially believable ones, is difficult. Living with real people and oneself is hard enough. But beyond this, what is our interest, our obsession even, with character. What exactly are we trying to work out – or resolve – through these people we create?

I thought of the book I have just written, and the book I am presently writing. Both are about values, particularly in situations where inherited corruption and abuses of race and history are present from the very beginning of an individual character’s consciousness, and how these mechanistic forces leave their imprint on the individual. They are both set in Africa, where one has many opportunities to feel the pressure of history and politics, and to consider one’s position. It’s impossible not to ask, in Africa, who has rusted so that I can prosper?

The other reason I’m thinking about conscience is more personal. Not long ago someone behaved in a way toward me that, while not outwardly shocking or violent, displayed a lack of conscience, among other things. In some ways this event has rippled through my life more powerfully than any dramatic or frightening occurrence I’ve experienced. I’ve had to search deep inside myself for the reason why I feel this way, and can only conclude that I have been operating with a moral code, or an idea of fair behaviour, that I was to a degree unaware of yet have internalised this in my conscience. Perhaps I even staked my life on it.

To get back to the project of writing a novel, conscience is not a necessary ingredient for consciousness, although if you reverse the two a different relationship applies. It is impossible for an unconscious being to have a conscience, yet so much of our lives seem devoted to the aestheticisation of our true conscience, and to the creation of a false self – a betrayal of conscience.

In a recent article for The Guardian, Rachel Cusk defends the kinds of creative writing courses on which I teach (Cusk also teaches, at Kingston University). She argues that the popularity and appeal of creative writing courses might have less to do with the desire to become a published novelists, and more to do with people’s famished need to speak with and of a ‘true’ self: ‘What is it, this book everyone has in them?’ Cusk asks. ‘It is, perhaps, that haunting entity, the ‘true’ self. The novel seems to be the book of self.’ The would-be writer, Cusk suggests, is only that person trying to free him or herself from a prison of false expression which ordinary life has forced upon him.

The arena of self-expression and the arena of conscience are linked. Life as it is lived gives ample opportunity to discover your own principles, limits, fallacies, values and beliefs. But writing fiction is a way to extend the boundaries of that arena, and to think abstractly about what people will do and what they will not do, to draw the frontiers of empathy and understanding, and consider how events take us to inhabit simultaneous doppelganger selves, masqued alter egos who might, in the terrain of morality and assumption, never existed. In a nutshell: a good woman is made bad. The transformation is incomplete, though. She is both at once. The story is, why?

In class last week, we wondered if using the novel to explore conscience was now old fashioned. The novel in its modernist sense – ie post-Conrad, Henry James introduced psychology (or psyche, as the better term) as a definitive factor in peoples’ fates. Their goal seems to have been to explore the intricate fabric of choice, tendency, happenstance, circumstance, politics, fate, that collude to create what many of us think of as our fate. The external will of God, or some other determining deity, has played a very minor role in these investigations in the last fifty years.

Cusk does not say this in her piece, but her argument suggests that conscience might live in the writer’s idea of their true self, and that conscience risks being eroded by ‘life’. Instinctively, I agree with her about the core self, and the need to speak the truth and be heard. This careful listening is perhaps what my Masters and PhD students get from me which is most of value (and which I never had myself; I always wrote in isolation).

But what is it about so-called ordinary lived experience that nudges us into dishonesty and betrayal of our core selves? Some of this is obvious: the doublespeak of corporate and bureaucratic life, the envy factory of Facebook and other forms of social networking where we put forward heavily edited versions of the self; the compromise of family life; the indignity of bodily failure, the weak-willed gamesmanship of human relationships. ‘Writing feels like the opposite of being alive,’ Cusk observes.

Writing is a way to get beyond – rather than escape – the self. This is one of its great emancipations. For having transcended the boundaries of the compromised public self, writers become mulish, durable thinkers, not easily manipulated, non-conformists with a simultaneously unbreakable and flexible sense of self. Mr James may have agreed that could be worth the effort of our often lonely fascination with the dimensions of the human spirit.